Tucked into President Donald Trump’s trade deals formalizing higher tariffs on goods from Asia this week are provisions for a global economic frontier the US wants to stay free of protectionism: digital commerce.

In deals with Malaysia and Cambodia, and a more preliminary agreement with Thailand, the White House received assurances none will impose digital services taxes or discriminate against American providers of e-commerce, social media, streaming, cloud storage or other types of online services. Those activities count as digital trade when the transactions cross national borders.

While Trump wields tariffs to rebalance US deficits in merchandise trade, his push for a global internet free of import duties and other surcharges is aimed at ensuring the world’s largest economy remains the leading net exporter of e-services. That stands in contrast with the prior administration under Joe Biden, which was more sympathetic to European officials’ concerns about unfettered access to markets for US tech giants including Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Meta Platforms Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.

“The Trump administration believes that our deficit in trade in goods has been unfairly imposed, but that our surplus in trade in services has been fairly earned” and wants to “maintain our services surplus, while reducing our goods deficit,” said Anupam Chander, a professor of law and technology at Georgetown Law in Washington. “I could understand why other countries would feel that this is itself unfair.”

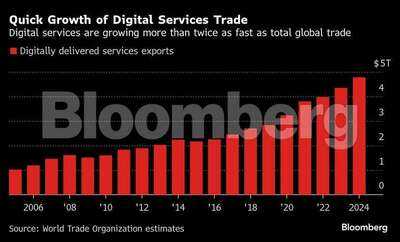

Last year, global exports of digitally delivered services increased to more than $4.77 trillion, a nearly 10% jump from 2023 and more than double the growth in total goods and services trade, according to World Trade Organization and United Nations figures. It’s the fastest-growing segment of global goods and services trade that reached about $33 trillion last year.

Supercharging digital trade is artificial intelligence, raising questions for officials concerned about national security, data sovereignty, intellectual property abuse and consumer privacy protections as online services flow unchecked across borders.

For some nations, it means a loss of government revenue as items formerly shipped as goods – a book or a movie, for example – are now sent digitally and out of reach of traditional customs duties.

As Trump tries to rewire the global trading system, digital commerce has become another battleground for geopolitical fragmentation where Washington and Beijing are jockeying for influence across Africa, Latin America and South Asia.

The new US provisions for Malaysia, Cambodia and Thailand stand out because they call for long-term acceptance of an agreement forged at the WTO calling on all countries to refrain from putting tariffs on digital services.

All three Southeast Asian economies agreed to support a permanent extension of the WTO accord known as the “moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions.”

Aside from that initiative and another aimed at protecting fisheries, Washington has abandoned the WTO – the referee of the rules-based trading system for the past 30 years - in favor of Trump’s unilateral approach with so-called reciprocal tariffs.

Global Agreement

The WTO moratorium has been extended by consensus every two years since 1998, most recently in 2024 when it only was approved in a last-minute deal held up by objections from India. It comes up for renewal again heading into the Geneva-based organization’s ministerial meeting in March 2026 in Cameroon.

“The commitments in the US deals to facilitate the free flow of data are absolutely welcome – especially when set against the trend for localization requirements that we’ve seen in recent years,” said Andrew Wilson, deputy secretary-general for policy at the International Chamber of Commerce. “While country-by-country progress is valuable, the ultimate goal should be to anchor these norms in a new international deal.”

Malaysia’s accord with Trump included the additional concession that it will refrain from “requiring US social media platforms and cloud service providers to pay into Malaysia’s domestic fund.

The latest digital pacts by the US – plus a preliminary one with Vietnam that contains a vague pledge to finalize digital services commitments — follow a framework the US announced in July with Indonesia, whose customs agency had preemptively added a line for digital services in its harmonized tariff schedule, or HTS.

That deal specified that “Indonesia has committed to eliminate existing HTS tariff lines on ‘intangible products’ and suspend related requirements on import declarations,” according to the White House document.

Under Trump, the US push for a permanent extension will have to address concerns from Brazil and India, both of which have faced some of the steepest US tariffs. In the past, both have wanted to preserve the option of raising revenue from foreign tech companies and protecting domestic e-commerce companies. Keeping the moratorium renewable also gave them leverage in other areas of trade.

“That extension looked very shaky after the last ministerial conference,” said Simon Evenett, a professor of geopolitics and strategy at IMD Business School in St. Gallen, Switzerland.

US Big Tech

Still, he said, while the US uses its leverage to push for a permanent extension of the moratorium, “it’s too soon to say this represents broad-based WTO re-engagement — more likely, it’s selective engagement on a topic critical to US big tech.”

Digital services provisions are part of most modern trade agreements, though the US and European Union have different views on the need for openness.

Officials in Brussels want safeguards against anti-competitive behavior and stricter data privacy protections — oversight that US officials consider over-regulation. Some European countries have annoyed Washington by imposing taxes on digital services, viewing such moves as domestic fiscal policy that’s outside the scope of trade talks. French lawmakers earlier this week voted to double a tax on large technology companies, risking a backlash from Trump.

The US-EU trade framework dated Aug. 21 noted both sides “commit to address unjustified digital trade barriers” and will together pursue a permanent WTO’s e-commerce moratorium.

Martina Ferracane, an associate professor of international digital trade at Teesside University in the UK, said another temporary extension is likelier than a permanent one because the US administration has “weakened its credibility” to lead a global consensus on the issue.

She cited Trump’s pledge to put 100% tariffs on films made outside the US as an example of a “threat of non-compliance” with the international ban on tariffs on digital commerce.

In deals with Malaysia and Cambodia, and a more preliminary agreement with Thailand, the White House received assurances none will impose digital services taxes or discriminate against American providers of e-commerce, social media, streaming, cloud storage or other types of online services. Those activities count as digital trade when the transactions cross national borders.

While Trump wields tariffs to rebalance US deficits in merchandise trade, his push for a global internet free of import duties and other surcharges is aimed at ensuring the world’s largest economy remains the leading net exporter of e-services. That stands in contrast with the prior administration under Joe Biden, which was more sympathetic to European officials’ concerns about unfettered access to markets for US tech giants including Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Meta Platforms Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.

“The Trump administration believes that our deficit in trade in goods has been unfairly imposed, but that our surplus in trade in services has been fairly earned” and wants to “maintain our services surplus, while reducing our goods deficit,” said Anupam Chander, a professor of law and technology at Georgetown Law in Washington. “I could understand why other countries would feel that this is itself unfair.”

Last year, global exports of digitally delivered services increased to more than $4.77 trillion, a nearly 10% jump from 2023 and more than double the growth in total goods and services trade, according to World Trade Organization and United Nations figures. It’s the fastest-growing segment of global goods and services trade that reached about $33 trillion last year.

Supercharging digital trade is artificial intelligence, raising questions for officials concerned about national security, data sovereignty, intellectual property abuse and consumer privacy protections as online services flow unchecked across borders.

For some nations, it means a loss of government revenue as items formerly shipped as goods – a book or a movie, for example – are now sent digitally and out of reach of traditional customs duties.

As Trump tries to rewire the global trading system, digital commerce has become another battleground for geopolitical fragmentation where Washington and Beijing are jockeying for influence across Africa, Latin America and South Asia.

The new US provisions for Malaysia, Cambodia and Thailand stand out because they call for long-term acceptance of an agreement forged at the WTO calling on all countries to refrain from putting tariffs on digital services.

All three Southeast Asian economies agreed to support a permanent extension of the WTO accord known as the “moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions.”

Aside from that initiative and another aimed at protecting fisheries, Washington has abandoned the WTO – the referee of the rules-based trading system for the past 30 years - in favor of Trump’s unilateral approach with so-called reciprocal tariffs.

Global Agreement

The WTO moratorium has been extended by consensus every two years since 1998, most recently in 2024 when it only was approved in a last-minute deal held up by objections from India. It comes up for renewal again heading into the Geneva-based organization’s ministerial meeting in March 2026 in Cameroon.

“The commitments in the US deals to facilitate the free flow of data are absolutely welcome – especially when set against the trend for localization requirements that we’ve seen in recent years,” said Andrew Wilson, deputy secretary-general for policy at the International Chamber of Commerce. “While country-by-country progress is valuable, the ultimate goal should be to anchor these norms in a new international deal.”

Malaysia’s accord with Trump included the additional concession that it will refrain from “requiring US social media platforms and cloud service providers to pay into Malaysia’s domestic fund.

The latest digital pacts by the US – plus a preliminary one with Vietnam that contains a vague pledge to finalize digital services commitments — follow a framework the US announced in July with Indonesia, whose customs agency had preemptively added a line for digital services in its harmonized tariff schedule, or HTS.

That deal specified that “Indonesia has committed to eliminate existing HTS tariff lines on ‘intangible products’ and suspend related requirements on import declarations,” according to the White House document.

Under Trump, the US push for a permanent extension will have to address concerns from Brazil and India, both of which have faced some of the steepest US tariffs. In the past, both have wanted to preserve the option of raising revenue from foreign tech companies and protecting domestic e-commerce companies. Keeping the moratorium renewable also gave them leverage in other areas of trade.

“That extension looked very shaky after the last ministerial conference,” said Simon Evenett, a professor of geopolitics and strategy at IMD Business School in St. Gallen, Switzerland.

US Big Tech

Still, he said, while the US uses its leverage to push for a permanent extension of the moratorium, “it’s too soon to say this represents broad-based WTO re-engagement — more likely, it’s selective engagement on a topic critical to US big tech.”

Digital services provisions are part of most modern trade agreements, though the US and European Union have different views on the need for openness.

Officials in Brussels want safeguards against anti-competitive behavior and stricter data privacy protections — oversight that US officials consider over-regulation. Some European countries have annoyed Washington by imposing taxes on digital services, viewing such moves as domestic fiscal policy that’s outside the scope of trade talks. French lawmakers earlier this week voted to double a tax on large technology companies, risking a backlash from Trump.

The US-EU trade framework dated Aug. 21 noted both sides “commit to address unjustified digital trade barriers” and will together pursue a permanent WTO’s e-commerce moratorium.

Martina Ferracane, an associate professor of international digital trade at Teesside University in the UK, said another temporary extension is likelier than a permanent one because the US administration has “weakened its credibility” to lead a global consensus on the issue.

She cited Trump’s pledge to put 100% tariffs on films made outside the US as an example of a “threat of non-compliance” with the international ban on tariffs on digital commerce.

You may also like

After Mokama killing, EC orders strict law-and-order checks in Bihar; full arms deposit drive

'Disgusting': JD Vance shuts down 'Hinduphobia' allegations, says he knows Usha has no plans to convert to Christianity but...

Delhi riots case: SC begins hearing arguments on bail pleas of Umar Khalid, Sharjeel Imam; next hearing Nov 3

Wildest Strictly Halloween outfits including daring gown

Check these 3 things before buying a used car, or you could face losses.